Modulation of Human Ankle Impedance during Walking

Motivation

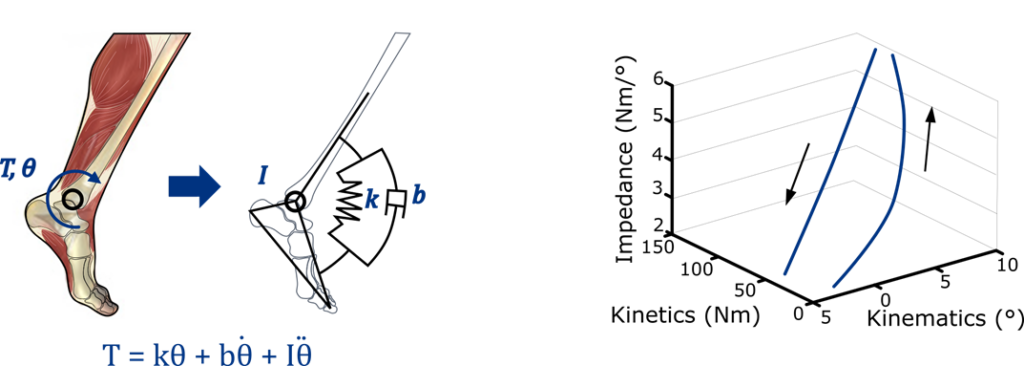

When we stand, walk or run, our brain and spinal cord send signals to our muscles to coordinate their movement. A combination of these signals and the physical properties of our limbs determines how we interact with the environment. One way to characterize this interaction is by measuring a property called joint impedance. Joint impedance determines the relationship between how a joint moves and the forces and torques it experiences. This relationship is commonly expressed as a combination of three parameters:

Stiffness (k) – Resistance generated due to the degree of a rotation.

Viscosity (b) – Resistance generated due to the speed of a rotation.

Inertia (I) – Resistance generated due to the acceleration of a rotation.

Many of the difficulties a stroke survivor experiences while walking are caused by changes in leg joint mechanics. Medically, these changes are referred to as hemiparesis, contracture, and/or spasticity and hypertonia. Mechanically these are analogous to changes in stiffness and viscosity. Studying how joint impedance is altered after injury or pathology and how different rehabilitation techniques affect this property could help us advance the standard of clinical care.

Most approaches in the development of robotic prostheses are focused on recreating how people move normally but do not consider how people respond to changes in their normal behavior. For example, how does someone change their behavior if they unexpectedly bump into another person, or walk on an uneven bit of ground? Expanding the control of such devices to include impedance would allow prosthetic device users to more naturally respond to such scenarios by providing more intuitive control of their device, increasing their stability and leading to more versatile mobility.

Approach

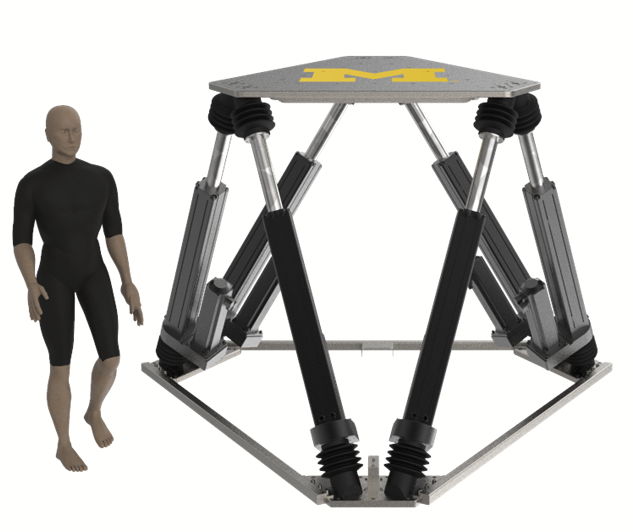

Experimental: For studying the ankle, participants walk or run across a walkway containing a robotic platform, termed the Perturberator robot. At various points throughout the stance phase, the Perturberator applies small rotations to the ankle. We measure the motion of the ankle using motion capture or a goniometer, and the forces applied by the person on the ground using a force platform attached to the Perturberator robot. We use the position of the ankle and the forces being applied on the ground to measure the torque generated about the ankle.

Analytical: As the participant walks across the platform they change their ankle angle and torque. This change is a combination of the natural motion of their body and their response to the motion of the platform. To estimate ankle impedance we separate these components by subtracting the torque-angle profiles occurring naturally during gait from perturbation trials. Impedance parameters – stiffness, viscosity and inertia – are estimated using mathematical models.

HEXAPOD Robot

The Neurobionics lab worked with industry partner to develop an in-ground, perturbation hexapod robot. This system will allow us to study the joint impedance of the entire leg (hip, knee, ankle) simultaneously. This Hexapod, which is recessed into a large pit beneath the floor, can rapidly move the floor beneath the research participant in three translational axes and two rotational axes. The system is integrated with the lab’s motion capture system, allowing precise timing and measurement of the perturbation and the human’s response.

Many research studies with wearable robotics focus solely on steady and rhythmic tasks, such as walking on a treadmill or from one side of a lab to the other. While these tasks are important, walking outside of the lab frequently occurs in much less structured environments such as over grass, rocks, or unexpected LEGOs. These types of uneven terrain commonly found in the “real-world” make the gait cycle deviate from its normal patterns, which we call “perturbations”. Understanding how both humans and human-robot systems respond to these perturbations is crucial for developing wearable robotic devices fit for real-world ambulation. Using different programmed trajectories, we plan to utilize the HEXAPOD system to simulate walking outside of the lab.

While technical publications using the Hexapod are still in development, we have already used this system to study walking, jumping, and the Open-Source Leg (see videos below).

Contributors: Kevin Best, Hannah Frame, Varun Joshi, Amanda Shorter, Elliott Rouse.

Publications

Shorter A. L., Richardson, J. K., Finucane, S.B., Joshi, V., Gordon, K.E., & Rouse, E. J. (2021). Characterization and Clinical Implications of Ankle Impedance During Walking In Chronic Stroke, Nature Scientific Reports, 11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-95737-6

Shorter, A. L., & Rouse, E. J. (2018). Ankle Mechanical impedance during the stance phase of running. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, 26(1), 135-143. doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2019.2940927

Shorter, A. L., & Rouse, E. J. (2018). Mechanical impedance of the ankle during the terminal stance phase of walking. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, 26(1), 135-143. doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2017.2758325

Lee, H., Rouse, E. J., & Krebs, H. I. (2016). Summary of Human Ankle Mechanical Impedance during Walking. IEEE Journal of Translational Engineering in Health and Medicine, 4, 1-7. doi/org/10.1109/JTEHM.2016.2601613

Rouse, E. J., Hargrove, L. J., Perreault, E. J., & Kuiken, T. A. (2014). Estimation of human ankle impedance during the stance phase of walking. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, 22(4), 870-878. doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2014.2307256

Rouse, E. J., Hargrove, L. J., Perreault, E. J., Peshkin, M. A., & Kuiken, T. A. (2013). Development of a robotic platform and validation of methods for estimating ankle impedance during the stance phase of walking. ASME. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering, 135(8), 081009. doi.org/10.1115/1.4024286